Lagos, Nigeria

In Lagos and estimated two-thirds of the citiy’s 23 million inhabiltants live in informal settlements, with a lack of security of tenure a defining characteristic. Without it residents live in constant fear of eviction. However, skyrocketing growth in Lagos has led to conflicts over land, often resulting in violent attacks on poor communities and a continued threat of mass evictions of the urban poor across the city.

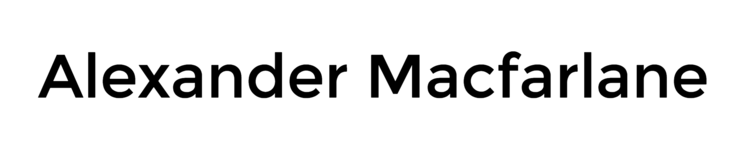

In November 2016 more than 30,000 people lost their homes when they were forcibly evicted from their community of Otodo Gbame. Eyewitnesses told how ‘area boys’ (local hoodlum) armed with machetes were sent into the community to douse the buildings in petrol before setting them ablaze. The police then entered, shooting at residents and forcing them to flee to the water where many drowned. Finally, bulldozers were used to demolish homes, schools, churches and other community buildings.

Many residents believe that the powerful Elogushi family who claim ownership over a tract of land that includes Otodo Gbame were behind the evictions.

In January 2017 a Lagos State High Court judge ruled that the waterfront evictions were cruel, inhumane and degrading. Residents have begun returning and commencing the rebuilding process following the destruction.

Evictions and the resultant loss of homes leave residents as refugees in their own city. Following the evictions in Otodo Gbame, residents from Sogunro, another waterfront informal settlement, travelled through the lagoons of Lagos in boats to collect and accommodate evictees in their own homes.

Residents from Otodo Gbame have suffered greatly, and in many cases have become separated from family. Meanwhile, the already densely populated host-community of Sogunro has been strained by the sudden growth in population. Overcrowding has led to illness and disease outbreaks, though there is no government health centre within the maze of waterfront buildings.

Some residents are slowly starting the process of moving back and rebuilding Otodo Gbame, though the threat of evictions remain for all waterfront communities in Lagos, including Sogunro.

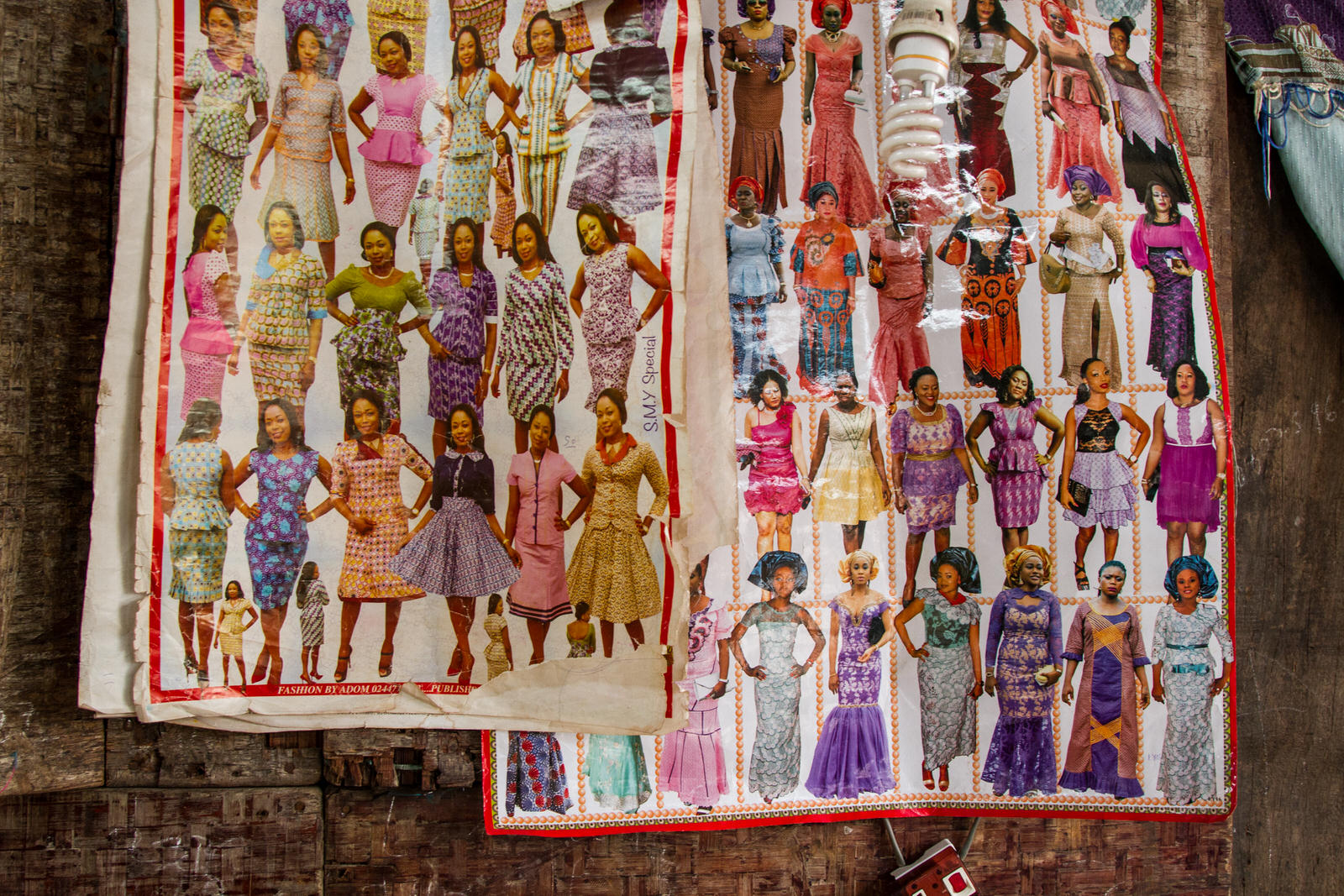

These photographs portray the communities of Otodo Gbame and Sogunro, and tell the stories of the hosts and evictees who have become refugees in their own city.